No one who is in the process of writing a dissertation knows how to write one; it’s just enough different from other genres that it’s a new process. And, since very few people write more than one dissertation, it isn’t a genre that anyone is very likely to master. I remember spending the whole time I was writing it with no sense of what I was writing. And then I was supposed to turn it into a book, and I’d never written a book, so the sensation of trying to master a game I’d never played before continued. I could try to rely on my sense of the genre of academic book—I did read an awful lot of them, after all—but that put me in the position of knowing the product and not process. And, as it happened, I picked the wrong product anyway. The books that I admired and wanted to emulate were third or fourth books written by well-known scholars whose learning and reputation meant that they were both able and allowed to use much broader strokes than would be allowed in a first book. Thus, I was trying to write the wrong book the wrong way; it didn’t go well.

Robert Pirsig tells a story in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance of a student who wanted to write a short paper about Montana, but suffered from writing block. Pirsig kept telling her to narrow her focus, till she was writing about one brick on the face of one building in a downtown area. Then she had no problem writing. Like Pirsig’s student, once I significantly scaled back my topic, claims, and audience, I was able to write much more and much more effectively. Recently, while working with graduate students, I was trying to figure out when it was that I learned how to write a book—it certainly wasn’t while I was writing my first one, but somewhere during the second. Then the question became just what it was I learned, and I think I learned how much I can get done and when. In other words, I learned to plan backwards.

Robert Pirsig tells a story in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance of a student who wanted to write a short paper about Montana, but suffered from writing block. Pirsig kept telling her to narrow her focus, till she was writing about one brick on the face of one building in a downtown area. Then she had no problem writing. Like Pirsig’s student, once I significantly scaled back my topic, claims, and audience, I was able to write much more and much more effectively. Recently, while working with graduate students, I was trying to figure out when it was that I learned how to write a book—it certainly wasn’t while I was writing my first one, but somewhere during the second. Then the question became just what it was I learned, and I think I learned how much I can get done and when. In other words, I learned to plan backwards.

The two time management books I recommend most frequently are David Allen’s Getting it Done and Steven Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. Because they operate from nearly opposite premises, the two books nicely complement each other—if one doesn’t work for you, then the other one probably will. Loosely, Covey’s book works from big goals down to daily tasks, and Allen’s book works in the opposite direction, from listing every small task. It seems to me that, despite the different premises, they work well together, at least for academics. Covey’s strategies are good for ensuring that the long-term projects get reflected in day-to-day planning, and Allen’s are good for keeping track of smaller autonomous tasks. One of his best pieces of advice, I think, is to externalize your memory—not to try to remember things, but to write everything down.

Academia has some very firm deadlines, such as when final grades are due for a class, and some that are fairly firm, such as class time (you’re either prepared for class by the time it starts or not), and a lot that are flexible up to a point (although one can set one’s own schedule for returning student work, if it isn’t done in a fairly timely manner, there should be ugly consequences). With some of the tasks, there are no externally established intermediate deadlines; in many graduate programs, there are no deadlines between a time at which one must have entered candidacy in order to maintain funding and when one must file the dissertation. Getting through undergraduate and graduate coursework does not necessitate learning the skill of setting one’s own intermediate deadlines (although I’d argue that skill is useful during undergraduate and coursework); finishing a dissertation is painful (but possible) without that skill, and it becomes extremely important for finishing a first book, and absolutely necessary for finishing a second.

Many people know that they should set intermediate goals, but they don’t know what those goals are, or how to ensure that they’re reasonable. Since writing a book seems impossible at the beginning (I still have stretches of time when I cannot imagine that what I am doing will result in a book), setting intermediate goals for writing a book means figuring out the stages in a journey to an unknown destination.

What I learned was not how to set that destination, but how to do that sort of planning. It means setting (or acknowledging) the deadline, and then articulating exactly what I have to have to meet that deadline. It can be helpful to distinguish between the ideal and the minimum. So, for instance, for a graduate student, it would be ideal to complete the degree in the spring of the final year of funding, with an article published in a refereed journal, a book review, and a number of conference presentations. The minimum is more likely to be filing the dissertation by the summer deadline. For assistant professors, it is crucial to know what the tenure deadlines really are, and that can only be inferred from recent practice—whatever you were told when hired isn’t worth the paper it wasn’t printed on. It’s sensible to try to overshoot the tenure standards, in case they change, or there is some kind of delay. Thus, if one is supposed to have a certain number of articles by the time one goes up for tenure, one should not assume they’ll get done in the last two years—getting them done earlier not only gives a person a cushion if plans collapse, but gives one career mobility. Academic publishing in the humanities is a very slow process; it can be a year between when the final version of the manuscript is submitted and when it is in proof pages, let alone published. So, if a book “in press” is expected for tenure (which is usually at the end of one’s fifth year), then a completed manuscript is necessary in the third.

But, that isn’t really an intermediate goal, just an intermediate deadline. Since many assistant professors have trouble working on their project precisely because they can’t grasp the project, moving up the deadline just increases the panic without giving any more information about the process. While it’s probably impossible to know exactly what the final version of a book will look like, as it will necessary change during the research process, it is possible to do a rough sketch of the number and topics of the chapters. Similarly, while one can’t know ahead of time exactly how many articles research will generate, it is possible to make an initial estimate. Most scholarly books are between 75 and 100,000 words (that is a price point for publication, so presses are hesitant about any manuscript longer than that); most journal articles are between 7 and 10,000 words (with that latter number being on the long side). Since readers will always ask for more, and rarely suggest what can be cut, a book or article manuscript should be well within the upper limit.

Given those numbers, one can make rough guesses about what the book might look like—six chapters of 10-15k words (an introduction and conclusion and four body chapters); or perhaps five body chapters of 15-17k words and shorter introduction and conclusion; or perhaps the introduction and conclusion will be worked into the material, so that there are six body chapters. If tenure requirements are articles, then one can similarly make educated guesses about how many articles one get out of one set of data.

The mistake that people tend to make about this kind of planning is to plan for chapters or articles that are too diverse from one another. This is a mistake in several ways. First, it obligates one to master a new set of secondary for each chapter/article. Second, if they are very diverse, the text may end up with multiple primary audiences, and that’s fairly ambitious for a first book. Of course, being too narrow also has problems; in my field, there is little demand for texts about just one author, and it seems to me that the day of the highly specialized scholarly monograph is over. The solution is not to try to strike that balance in the early stages of sketching the project; instead, come up with a stretch and talk to editors, colleagues with strong publication records, and mentors to see if there is interest in its current form. The goal is to talk to editors who go to the conferences you go to, not necessarily the presses with the most prestigious names. You can also look to see what press publishes most of the books you use in your research—that indicates it’s a topic about which they publish. Sending out a prospectus early is unlikely to get an advanced contract (especially for first books, presses usually want to see a completed manuscript) but will give early feedback about the project.

If one can get clear about the tenure standards at one’s institutions (which is more or less difficult at various places) then it’s more straightforward to backplan. In addition, the process of publication can be confusing. For a book, an author might submit a query or prospectus (submitting a query to a journal editor is recommended in some fields). Each is a brief summary of the text (in the case of a query, it’s the abstract) with page length and, in the case of a book, date of expected completion, manuscript status (how many chapters are finished). The exact parts of a prospectus vary from press to press, and an author should check “submission guidelines” for each press. While it is fine to submit a prospectus to multiple presses, it is generally considered bad form in many fields to submit the manuscript to more than one press at once. If the editor is interested, s/he might send the prospectus out to readers, or to the editorial board, or simply review it. An author might get an advanced contract, but, for a first book, an author is more likely to be told whether the press is interested at all. If interested, they will probably want to see the completed manuscript. For article and book manuscripts, one should follow the “submission guidelines” for the specific journal or press. If the manuscript seems appropriate to the press’ list or the journal’s audience, and the press/journal is not already over-committed, the editor is likely to send the manuscript to readers.[1] The readers might take as long as six months to review the manuscript. People, including me, complain about how slow this process can be, and six weeks is plenty of time to review an article (and four months for a manuscript), readers don’t always respond as quickly as we should.

Readers will respond to the editor with a recommendation that the text be accepted as it is, accepted with minor revisions, resubmitted with major revisions, or rejected. They will include a set of comments describing the reasons for their decision, and, if suggesting revisions, a description of what those revisions are. The editor sends those comments to the author (usually called readers’ reports), along with a statement of his/her decision. If the text has been sent out to readers, even a rejection gets an author useful information about how audiences are likely to react to the piece. Sometimes an author decides that the readers have useful advice, and sometimes s/he decides they don’t. If the suggested revisions take the piece too far away from where the author wanted, s/he might choose not to revise and resubmit to that press/journal, and may instead submit it unchanged elsewhere. If the article is rejected, the author might choose to revise on the basis of the readers’ reports, and then submit a revised version to a different press/journal. Some authors find it useful to share the reports and the manuscript with a mentor or colleagues, especially if (as they often do) the two or more reports seem contradictory.

If the author has been given a “revise and resubmit,” it is generally a good idea to communicate with the editor about one’s plans—paraphrase the major concerns of the readers, describe how those concerns will be addressed, and give a timeline. An email is usually adequate, and it is helpful if it is in a timely fashion. Even the decision not to revise and resubmit is useful for an editor to know. Once the manuscript is revised, then it’s resubmitted, possibly with a cover letter explaining what changes one made. The manuscript usually goes out to readers again; if possible, to the same readers (but that isn’t always possible). If the responses are positive, the editor may be willing to write a contract. While most publishing contracts give more leeway to the press more than the author—they don’t actually obligate the press to publish the piece, but they do obligate the author to publish it there—they are tremendously useful for promotion. It is rare, in my experience, for a press to renege on a contract, although they do sometimes delay publication (in cases of financial exigency). The contracts for academic books usually have fairly minimal royalties, and it’s common for a scholarly press book to sell only around five hundred copies, so some authors are surprised at the terms of the contract—scholarly publishing (unless it’s textbooks) is not especially profitable for most people (including the presses, which often run at a deficit).

The author may be asked to revise one more time, but presses are hesitant to send a manuscript to readers a third time. Once the truly final manuscript version is sent in, the press sends it to a copy-editor, and then the author gets back a copy-edited version. It may take two to three months for the copy-editing to happen, and the author rarely has much time to check it. As with proofing, it is intense, time-consuming, and difficult. After the author checks the copy-editing (accepting or rejecting the suggested changes), the press has the manuscript put into proof pages. The author is responsible for proofing the pages, usually at the same time that the index is being prepared. Some authors choose to do both; some hire an indexer; some allow the press to hire an indexer (the cost of which comes out of the royalties). Since both copy-editing and proofing have to be done quickly, and are very time-consuming, it’s helpful if the author can schedule time for it—communicating with an editor about a timetable benefits both parties. Because the index is being done at the same time, the author should not alter the manuscript in a way that throws off the pagination. That would require the press to cover the cost of repagination (which is not trivial). The author should be looking for typos, not ways to edit the manuscript. Once the proof pages are returned to the press, it may be anywhere from three months to a year before the book appears (depending on the press).

For articles, the process may be slightly different. Some journals expect that the author will do the copy-editing, and the process of both copy-editing and proofing are much faster. Because editors are trying to keep issues balanced in terms of length (and may be trying to balance individual issues in terms of topic, audience, and other concerns), it is very helpful to them if authors stick to deadlines. It is not all the same to an editor if one gets a manuscript to them somewhat later than one promised.

Given this schedule, there is a terminology for where in the process one is, and this terminology is important for hiring, tenure, and promotion. I’ll use terms as they’re defined at my institution by the College of Liberal Arts Committee and Promotion and Tenure:

· “Book in hand” means that the book (or articles) are actually out—“you can stop a door with it,” as my dean says.

· “Forthcoming” is the term used for a text (book or article) that has a specific publication date, set by the publisher; there is an explicit or implicit contract. It should not be used for manuscripts that are simply under submission.

· “In press” is even more specific than “forthcoming”—it means that the text is in the page proof stage or beyond.

· “Under contract” means that the author has a contract (I would use that even more specifically—it is a functioning contract, so if one has a contract with deadlines that one has missed by a year or more that isn’t really “under contract” any more.)

· “Under submission” is the broadest category, and means that one has submitted the text to a journal or press. For cvs and annual reports, it’s often advised that one specify if it has been revised and resubmitted. Some people advise sending off poor manuscripts, just to be able to claim that lots of things are “under submission,” but that strategy will backfire if anyone keeps track.[2]

· “In progress” is how people describe topics on which they’re currently working. While some fields strongly discourage job candidates or assistant professors from putting anything on the cv that isn’t complete, in other fields (mine included) that one is working on a particular topic is considered relevant information.

This terminology is not just important for the documents a scholar creates, but for being clear on the standards for promotion and tenure. Because of how slow the publication process is, if a candidate for tenure must have a “book in hand,” s/he should have a manuscript ready much earlier than if the standard is “under contract” or the extremely vague term “manuscript in hand.”

If you can make an educated guess as to the number of chapters your manuscript will have (or the number of articles you will write), then you schedule backwards from when they must be done. Here, for instance, is a possible long-term plan for completing a manuscript in time for promotion and tenure at an institution that requires a book “in press” for tenure. It presumes a fairly heavy teaching load, such that getting scholarship done during the “long calendar” is challenging.

Year | Book | Other |

1st year | Come up with a revision plan (calendar, reading list, description of changes); read; makes notes about a potential second project | Figure out where the grocery store is; draft a repertoire of classes; two conferences directly related to this or your next project |

1st summer | Article version of one chapter from the dissertation; submit by August 1. | The impulse is to teach summer school, as the money would be very helpful, but that would make the goal of completing a chapter extremely difficult to achieve. |

2nd year | If there is a new body chapter, write it—start with whatever part of the dissertation requires the most new work/reading/writing. NOT your introduction or conclusion. | Two conferences directly and clearly related to this or your next project. |

2nd summer | Revise the body chapter that requires the second most new reading/writing. Polished version by August 1. | Same caveat as above about teaching summer school. |

3rd year | Revise body chapter and submit prospectus to between 4 and 7 presses. | Two conferences directly and clearly related to this or your next project. |

3rd summer | Revise remaining body chapters. | Same caveat as above about teaching summer school. |

4th year | Revise intro and conclusion. Submit completed ms. to press by June 1. | Two conferences directly and clearly related to this or your next project. |

4th summer | Article version of new project; submit by August 1. | Teaching summer school is a possibility only if you can definitely do it and the article. |

5th year | (Should hear back from the press by November; till then work on your next project.) If rejected, then resubmit (after, at most, two months spent on revisions). If you get a revise and resubmit, then draft a revision plan (with consultation with colleagues, your diss chair, people you know from conferences) and get that plan to the press within two to four weeks. Revise. | During all the “down” time on this project (e.g., when it’s being read by the reviewers, while it’s being copy-edited), work on designing and planning the next project. |

5th summer | Submit revised ms. by July 1. Prepare tenure case. | |

6th year | Go up for tenure. |

Possible calendar for promotion and tenure at a university that requires a book “in hand” for promotion to associate professor:

Year | Book | Other |

1st year | Come up with a revision plan (calendar, reading list, description of changes); read; makes notes about a potential second project | Figure out where the grocery store is; draft a repertoire of classes; two conferences directly related to this or your next project |

1st summer | Article version of one chapter from the dissertation; submit by August 1. Revise one body chapter. | Even though someone on this schedule has more time, I still recommend against teaching summer school, at least until the publication record is secure. |

2nd year | If there is a new body chapter, write it—start with whatever part of the dissertation requires the most new work/reading/writing. NOT your introduction or conclusion. | Two conferences directly and clearly related to this or your next project. |

2nd summer | Revise the body chapter that requires the second most new reading/writing. Polished version by August 1. | Same caveat as above about teaching summer school. |

3rd year | Revise remaining body chapters and submit prospectus to between 4 and 7 presses. | Two conferences directly and clearly related to this or your next project. |

3rd summer | Revise intro and conclusion; submit completed ms. by August 1. | Same caveat as above about teaching summer school. |

4th year | You should have readers’ reports by Jan 1 at the latest. If rejected, then resubmit (after, at most, two months spent on revisions). If you get a revise and resubmit, then draft a revision plan (with consultation with colleagues, your dissertation chair, people you know from conferences) and get that plan to the press within two to four weeks. Then revise. If asked to revise and resubmit, then resubmit ms. by July 1. | Two conferences directly and clearly related to this or your next project. |

4th summer | Article version of new project; submit by August 1. | |

5th year | Work on revisions on article; copy edit ms. | Two conferences on whatever you want. |

5th summer | Work on next project. Prepare tenure case. | |

6th year | Go up for tenure. |

I will emphasize that all of that advice could be criticized as arbitrary—five year calendars always have enough guesses that the final version is necessarily somewhat arbitrary—and that plenty of people have been successful with very different calendars. It presumes, as mentioned above, a heavy teaching commitment, and some universities give new faculty reduced teaching loads. The advice about summer school is the most controversial, and is admittedly cautious. If someone is making good progress during the long calendar (able to get two chapters done, for instance) then it would be excessively cautious. What this calendar is trying to prevent is the classic time management arrangement of the bulk of one’s time spent on teaching for the first three years and on scholarship for the second three. That arrangement is, at best, risky, and an ill or dilatory editor, bad luck in terms of the outside reviewer, financial troubles at a press, or any of a dozen incidents could make it disastrous.

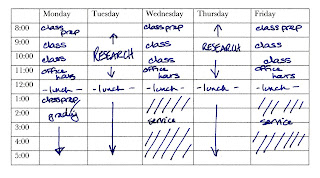

Most graduate programs have students teach one course per semester, and so graduate students can struggle at the transition to teaching two or three courses per semester. For those of us who teach writing, it’s extraordinarily difficult to keep teaching to some kind of reasonable amount of our schedule. At many universities, especially Phd-granting, faculty are told that the promotion to Associate Professor (and consequent granting of tenure) is 40% dependent on good teaching, 40% dependent on scholarship, and 20% dependent on service—some universities protect junior faculty from service, so that it isn’t taken into consideration at all. Some universities put little emphasis on teaching, so as long as one doesn’t leave the bodies actually in the classroom, a good publication record is all that’s necessary, and some universities have minimum expectations regarding publication but very high expectations regarding student satisfaction. Obviously, one would create a different weekly calendar with different promotion and tenure expectations. But, assuming the 40/40/20 split, a normal week should have two days (16 hours) spent on teaching, two days (16 hours) spent on research, and one day (8 hours) spent on service. If one is teaching two classes, that is six hours in class, and only ten hours per week of class preparation and grading. Those ten hours include office hours, usually required to be 3-4, during which time one might be able to get some class preparation done. That sounds like plenty of time, but it isn’t, especially if the classes are writing classes. If you try to turn this abstract set of principles about time commitments into an actual workweek, you can see that it initially can look fairly straightforward:

It quickly becomes complicated, however. I typically teach two writing classes per semester (at one institution, I taught three per semester). Hence, approximately once every three weeks, I have about 45 papers to grade, and it takes me 30-40 minutes per paper to grade them, or an additional 23 hours I need to find in a week. At least once per semester, I confer individually with each student for 20-30 minutes, so I lose another 20 hours that week. For six of the fifteen weeks in the semester, then, I will get no research done. Still, that should leave nine weeks in which I could work on scholarship for sixteen hours a week, plenty of time to get an article or chapter done per semester. And that isn’t what happens during most weeks for me—instead, I generally have four to five weeks in which I can do that much scholarship.

Burka and Yuen recommend that people make a schedule of what they actually do with their time (just as people dieting are advised to keep a food diary); they call it an “un-schedule.” As with the food diary, the difference between the schedule we think we should have and the one we really have can be surprising. Here is the one they show for a teacher, Marsha, who is having trouble returning students' midterm papers:

There are several things that are striking about it—notice that the schedule exemplifies the “double shift,” that she is cutting up her schedule in order to take the kid(s) to and from school, for instance. By cutting back on the time during the weekdays, she obligates herself either to make up that time evenings and weekends, or to have what is, in effect, a part-time job. Assuming no commute time whatsoever (that she can drop the kids off and get to work by 8, and leave work at 3 and still pick them up), and that she works through lunch (never a good idea), she works 8-3 five days a week, or 35 hours a week at most. That’s a problem. It’s even more of a problem if one looks at her actual schedule:

She is actually working just over twenty hours a week, very nearly a half-time job. No wonder she can’t get her grading done. This is a deeply problematic schedule for other reasons as well: there is no indication in the book that he is being paid for a half-time job; it’s suggested that she’s being paid for full-time work. While Burka and Yuen are supportive of the changes she is trying to make, and that’s probably the best stance for a therapist to take, someone needs to have a serious talk with her about her schedule. It’s unlikely that her department is filled with people working 25 hours a week, so colleagues are likely to be resentful (with reason, I think) if there is committee work that others are having to pick up—notice that she isn’t even doing as much service as is expected. If she is in a position in which scholarship is expected, this is a very grim schedule indeed.

One of the problems with the kind of free-form schedule that academics often have is that it is easy to lose track of how much time is spent on work, with the consequence that a person can be working either much less or much more than it seems. When I was in graduate school, a very productive friend explained that he got so much done because he worked 9-5. And when was working, he was really working, not just hanging out in the TA office whining about how much work he had to do (something I spent so much time doing that I should have gotten a degree in it). I was convinced that working 9-5 would be a reduction in the amount of time I worked—work seemed to loom over my life the way Godzilla looms over a city. After all, I was working evenings and weekends. Once I tried to make a schedule, however, I discovered that my sense of how much I worked was wishful thinking—in fact, I’d really start work at about ten a.m. (after I’d gotten coffee, read various things, sharpened pencils, and engaged in other forms of dithering), and work till about four p.m., with a couple of breaks for coffee and one for lunch. I’d work an hour or so most evenings and several hours on Saturday and Sunday. But, since I was working about 25 hours during weekdays, even picking up the evenings and weekend work got me to about 40 hours a week, or what I was actually expected to work (and what most of the taxpayers who paid my salary generally worked). I wasn’t exactly the long-suffering martyr I was imagining myself to be.

Although it’s far from the most common reason for academics to fail to get scholarship done, trying to get a full-time job done in part-time hours is one reason some people aren’t as productive as they’d like to be. If Marsha wants to work a 25-35 hour week, then she needs to scale her expectations for herself to that amount of time. And this is another piece of advice that gets people angry with me (or with anyone who gives the equivalent advice). There is, in fact, a limited amount of time in the day, but a potentially infinite number of things we would or could do with that time. It’s hard to imagine ways of increasing how much scholarship we get done that don’t necessitate spending more time on it. And, if we are going to commit more time to any task or goal, we have to spend less time on something else. If, like many of us, she wants to be an excellent parent, scholar, teacher, and colleague, and she can’t do it in 35 hours, she needs to find more time or decide to be less than excellent at one of those things. There is no point in beating one’s self up for failing to do the impossible, and it's impossible to spend more time on one task without reducing time spent on something else.

More common than the person who isn’t getting scholarship done because they aren’t working full-time is the person who is working more than full-time and still doesn’t have enough time for scholarship. This can be a time management issue in all sorts of ways--unreasonable expectations, only working on what's urgent, or various others. Paradoxically, it can be partially solved by reducing the overall time one spends on work. At another point in my life, I became aware that I was working eight hour days, and then working after dinner, and working three or four hours both days of the weekend. And when I wasn’t working, I was feeling guilty about the fact that I wasn't. This was a case when I didn’t need to work more, but I did need to work much more efficiently, and one way to do that was to be more rested when I was working. When I set Sunday and after dinner off-limits, so that I would not work during those times, I became more efficient with my other time. Granted, I sometimes got up awfully early in the morning, but that worked more effectively for me than staying up late. The soul needs rest.

As with the disparity between a food diary and an ideal diet, there are multiple ways of reconciling the real and the dream schedule. In addition to scaling back one’s goals, another is to make the ideal schedule more realistic. Particularly because of my obligations to the amorphous kinds of teaching—graduate students writing dissertations or in conference courses, undergraduates doing independent studies or theses—and partly because I put a lot of time into reading student material, I simply plan for twenty-three hours on teaching per week, and more for those weeks in which I’m grading. Were I an assistant professor with a book expected for tenure, that would be a professionally suicidal commitment. I would have to change my teaching strategies to make them much less time-intensive.

If one decides to go the other route, and make one’s real schedule more idealistic, Burka and Yuen recommend doing so over a long period of time—setting goals for how much time one spends on scholarship, and (at least visually) rewarding one’s self for moving toward those goals. From the perspective of a writing teacher, this makes tremendous sense—setting manageable goals, rewarding small progresses, and making those goals process rather than product. That is, many people would be tempted to set the goal of a product; instead of “I will work on scholarship an average of eight hours per week” to say “I will get an article published this semester.” Of course the first is framed as step toward the latter, but the former way of seeing the goal keeps the achievement within one’s own control much more than the latter. But it does mean that one has to set reasonable goals about one’s time, and then protect it (so we’re not entirely free from the possible interference of others). Hence, some people work at home if they tend to get interrupted on campus, but others find they get too many interruptions at home and so work on campus. Sometimes protecting one’s time means training other people (or, in my case, people and dogs) not to interrupt during certain periods unless their hair is on fire and no one else but you can put it out.[3] For the most part, the people I have known who had trouble finishing scholarship are people who have trouble setting aside and protecting that time.[4]

A third option is to procrastinate some of the many things one wants to do. I love teaching, and I would never have gone into this career if I couldn’t read student work carefully, get to know my students individually, and spend as much time on teaching as I do. But that doesn’t mean that every year has to have the same level of commitment. Some faculty have a difficult time saying no—to requests from administrators, colleagues, or students—so it may be easier to say, “Yes, but not now.” Restricting one’s commitment to teaching and service while an assistant professor doesn’t mean being a selfish jerk who doesn’t carry the same service load as others; it means focusing on this kind of work at this point in one’s life.

A fourth option is to protect larger blocks of time, such as a month. I have learned that September, the latter half of December, March, May, June, and half of July are times in which I can get a lot of writing done. Research leaves are, of course, the exception, but I have a caveat about those as well. Sometimes friends and family don’t understand the nature of a research leave (just as many don’t understand the concept of working at home), and will assume that time with a leave is a good time for travelling, DIY home improvement projects, keeping kids out of daycare, and all sorts of things other than working eight hours a day. Some scholars fall for that trap as well, and overschedule their own leaves so much that they couldn’t possibly put the time in that is necessary for scholarship.

I am a big believer in desk organizing products. I’m not sure how many sorters, hutches, baskets, little sets of drawers, and shelf sets I’ve bought over the years. They never work, of course, because I fail to put things in them consistently. But I still look with longing at cunning little products, as though that product would make all the crap on my desk leap into the right places. If I want a cleaner desk, I need to put things in the little products. I think the same thing happens with some people and leaves. Sometimes it seems to me that people who fail to set aside time in a normal year for scholarship assume that getting a leave will magically organize their time for them. A leave won’t organize their time anymore than a new hutch will organize my desk. Doing scholarship takes time; people have to commit the time to it.

All sorts of things (and people) keep scholars from committing time to their scholarship. One of them, ironically, is being a “good citizen” to the Department. Administrators, even one’s Department Chair, are not in the same role to an assistant professor as one’s advisor is during graduate school—they are not necessarily looking out for you, let alone for your best interest. That isn’t criticism of Department Chairs; I’ve never known one who wanted Assistant Professors to be denied tenure and promotion. It’s simply that they have other things to do that are, to be blunt, more important in the grand scheme of things than any individual in a department. So, while it can be very helpful to have periodic discussions with one’s chair about one’s career, don’t expect them to remember those conversations in much detail. Therefore, when a chair asks you to do something—to be on a committee, for instance—s/he hasn’t calculated whether, given your various other obligations, that service is the best use of your time. It is your job to look out for your time.

That doesn’t mean being a jerk; it means working out a rational plan, ideally with the consultation of your chair, regarding the kind and amount of service you will be doing while an assistant professor. Then it becomes your job, not your chair’s, to think about each additional request in light of that plan. Similarly, teaching obligations should be a reasonable negotiation among what the students need, what is convenient for you, what your department needs, and your research. In (too) many departments, the most loathed teaching assignments are dumped on assistant professors because they can’t say no. If that’s the case, then you may not have much control over how pleasurable at least that course is, so try to make sure at least one other course is related to your research (since, presumably, your research gives you joy).

I’m often surprised by the advice that is given by supposed teaching experts on how to improve teaching. For instance, a colleague in another department whose lectures on a difficult and fairly boring topic were, in fact, boring, was told to put all his lectures on powerpoint slides, that he was to read off of during class, and which he would make available via the web to students who hadn’t bothered to come to class. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that his evaluations, already weak, plummeted. Everyone has a bad semester from time to time, and one often has to teach a deeply problematic class (usually a required introductory class for students who would rather be doing anything other than be there). But it should be, on the whole, tremendously rewarding. If it’s going badly, then get help from people who do it well (not just one person).

If the only way to keep it from going badly is to spend too much time on it, then it might be useful to try to work with a good teacher on how to make one’s teaching more efficient—not in the sense of being more stream-lined, but in the sense of getting more bang for the buck. I don’t mean to give specific recommendations, but to persuade people that teaching, like scholarship, is something that is well-considered in a kind of big picture way. Thinking about one’s course rotation over a five-year period, for instance, and then spending the first year trying to develop a repertoire of classes and deep set of teaching resources (handouts, notes for teaching, assignment prompts) that can be refined rather than reinvented, is far more likely to lead to good teaching than developing a new course every semester (as I spent far too much time doing).

[1] Editors may ask an author to make recommendations for outside readers—different presses have different policies as to whether it must be someone unknown to the author. While the identity of the readers is unknown to the readers, the readers do know the author’s identity; this is not true of “blind-reviewed” journals, in which case neither author nor reader knows the identity of the other.

[2] And they might. Although graduate students and assistant professors are often advised to use the most eulogistic terms possible in the cvs and annual reports, and even engage in a little wishful thinking (listing as “forthcoming” something that is actually “under submission”)—that was certainly the advice I was given—I have seen fairly ugly consequences of that practice. My advice is to be as precise and accurate as one can.

[3] At another institution, I had an administrative position. I could spend all day sitting in my office and do nothing but handle whatever crisis arrived in the form of a person at my door or a phone call. When I moved some distance away and worked from home two days a week, and those same people would have had to make a long-distance call or send me email, they didn’t bother. Being accessible is over-rated.

[4] Ferrari and Dovidio, for instance, argue for a correlation between procrastinators and people who are easily distracted (“Examining Behavioral Processes”); certainly, while there are seem to have trouble focusing on a sufficiently specific topic, and whose writing processes is impeded by throwing more books to read in the way of writing, I’m not persuaded that they read those additional books because they’re distracted. When I was in graduate school, a friend pointed out that the male ABD students all had fastidiously –tended bears, and that most of us (I was the exception) had cleaner apartments than we ever had before. It seems to me that, for many people, the additional reading serves the same function as beard-trimming, cleaning out under the refrigerator, or taking up a new hobby have; it isn’t that a person is genuinely distracted by the detritus under the fridge. Such tasks are only attractive because they provide a mildly self-punishing way to procrastinate.

No comments:

Post a Comment